The quasar’s radiation could in turn influence the reservoir of gas in the galaxy, which provides the raw material for both black hole growth and star formation in the galaxy. Gas falling into the central black hole would transform the black hole into a quasar. Other scenarios have explored causal relationships between black hole and galaxy mass. The natural consequence after numerous mergers is that the galaxy mass will tend to the average mass of the initial galaxy population times the number of galaxies that were incorporated, while the central black hole mass will tend to the average mass of initial black holes, times the same number, leading to a roughly linear relationship. That proposal emphasizes the role of averaging effects: In the current cosmological scenarios, galaxies as a whole grow through the merger with and incorporation of smaller galaxies, and central black holes through the merger with and incorporation of those smaller galaxies’ central black holes. One proposal was recently worked out quantitatively by Knud Jahnke (an MPIA scientist involved in the research reported on here) and his colleague Andrea Macciò. Black holes and their galaxies: a common historyĪ fairly obvious assumption is that this relation between black holes and their galaxies has come about because of these object’s common history – that somehow, the same scenario that will lead to the formation of a galaxy with high stellar mass will also lead to the evolution of a more massive central black hole, and vice versa. Given that stellar masses of galaxies are so much larger – by about a factor of 1000 – than central black hole masses, that relationship, which holds for million-solar mass central black holes as well as it does for specimens that are 100,000 times more massive, is remarkable. If you plot these masses for different galaxies, there is a comparatively simple function (a power law) linking the two. Since the early 2000s, it emerged that there is a direct relation between the mass of a galaxy’s central black hole and the total mass of the galaxy’s stars. A key insight was that quasars are just the tip of the iceberg – every larger galaxy has a central, supermassive black hole, but most of them are not nearly as ostentatious as their quasar brethren (If you are following astronomy news, you will have seen the “image” taken of the shadow of our own galaxy’s central black hole that were published in 2019.) Since the discovery of the first quasar in 1963, astronomers have learned an enormous amount about these objects, from the mechanisms producing their intense radiation to their influence on their surrounding galaxies. Supermassive black holes and a curious relation It is not, at this point, clear what this means and how this comes about – but it is likely to be relevant for attempts to solve a persistent riddle about early supermassive black holes, namely how they managed to accumulate a comparatively large amount of mass in a comparatively short period of cosmic time. The early quasars the astronomers observed show the same relation. The observations show that, in one important respect, those early quasars and their host galaxies are very similar to modern galaxies: For modern galaxies, there is a direct correlation between the mass of a galaxy’s supermassive black hole and the total mass of the galaxy’s stars. Now a group of astronomers led by Masafusa Onoue, started when Onoue was a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, and using the James Webb Space Telescope, have managed for the first time to observe the host galaxies of quasars in the distant cosmic past, at a time when the universe was less than 10% of its current age.

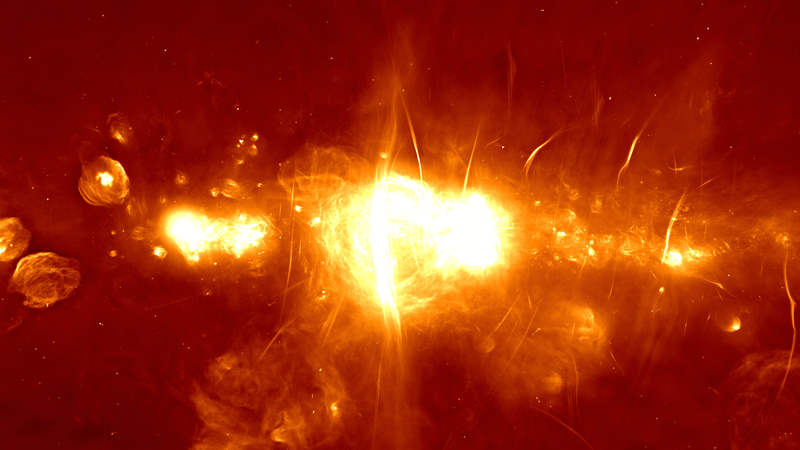

Quasars are some of the most extreme objects in the universe – they are among the brightest objects out there, outshining whole galaxies, and behind all that brightness is some of the most extreme physics we know: Quasar light is produced as gas falls into black holes at the centers of galaxies, and such supermassive black holes embody the mass of millions or even billions of Suns.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)